Introduction: Fasting as a Spiritual Discipline and Divine Guidance

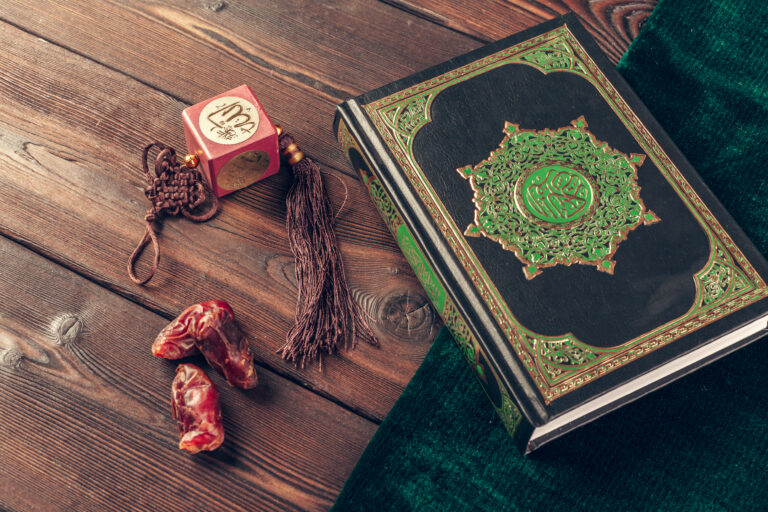

📖 “O you who believe! Fasting is prescribed for you as it was prescribed for those before you, so that you may attain self-restraint.” (Qur’an 2:183)

Fasting (Sawm) is one of the most emphasized acts of devotion in the Qur’an. While commonly observed as a full month, evidence suggests that the original fasting period may have been intended for ten days instead of an entire lunar month. It has been a central spiritual practice not only in Islam but also in previous religious traditions, such as Judaism and Christianity, where fasting was observed as a means of purification and devotion. It is not merely an abstention from food and drink but a comprehensive exercise in discipline, self-awareness, and spiritual purification. However, much like Salāt, the practice of fasting has undergone modifications over time, often deviating from its original Qur’anic prescription.

This article explores the Qur’anic understanding of fasting, its connection to Laylatul Qadr, the correct calendar methodology, and the appropriate fasting times.

1. The Purpose and Spiritual Essence of Fasting

📖 “The full moon of Ramadan is that in which the Qur’an was sent down – as guidance for the people and as clear proofs of guidance and distinction. Whoever among you witnesses this full moon, let him then fast. And whoever is sick or on a journey, then (fast) on a number of other days. Allah intends ease for you and does not intend hardship for you, so that you may complete the count, so that you may magnify Allah for having guided you, and so that you may be grateful” (Qur’an 2:185)

Key Observations:

✅ Fasting is a means of attaining self-restraint and heightened consciousness of Allah.

✅ It is directly linked to the month in which the Qur’an was revealed.

✅ It serves as a reminder of gratitude and discipline.

Unlike the common belief that fasting is a mere ritual, the Qur’an presents it as a powerful tool for self-mastery and divine awareness.

2. The Timing and Duration of Fasting

📖 “Fast for a limited number of days, but if any of you is ill or on a journey, then an equal number of days are to be made up later. And for those who are able to fast with hardship, there is a ransom: feeding a needy person…” (Qur’an 2:184)

Key Observations:

✅ The Qur’an refers to fasting as being for a ‘limited number of days,’ not necessarily a full month.

✅ The ten-day fasting period aligns with various historical practices of purification and devotion.

✅ A well-documented Sunnah practice is to fast an additional six days in the month of Shawwal, completing a total of ten days of fasting, reinforcing the idea that the core fasting period was originally ten days.

✅ The flexibility in making up missed fasts suggests that the emphasis is on intention and devotion rather than rigid duration.

📖 “Eat and drink until the white thread of dawn becomes distinct from the black thread. Then complete the fast until the night.” (Qur’an 2:187)

Key Observations:

✅ Fasting begins at the first light of dawn. Nautical observation leads to 1 hour and 36 minutes before sunrise around the timing of Fajr.

✅ It ends at night (not at sunset), which aligns with the natural disappearance of daylight.

✅ There is no mention of pre-dawn meals (suhoor) or an exact time for breaking the fast (iftar) apart from ‘the night.’

This clarifies common misconceptions regarding the timing of fasting and suggests that it should be governed by clear visual indicators rather than pre-set schedules.

3. Laylatul Qadr: The Most Valuable Night

📖 “Indeed, We revealed it on the Night of Decree (Laylatul Qadr). And what will make you understand what the Night of Decree is? The Night of Decree is better than a thousand months.” (Qur’an 97:1-3)

📖 “We revealed it in a blessed night. Indeed, We were to warn (humanity).” (Qur’an 44:3)

Key Observations:

✅ Laylatul Qadr marks the initial revelation of the Qur’an.

✅ It is a night of immense significance, surpassing a thousand months.

✅ The Qur’an does not specify a fixed date for Laylatul Qadr, which means it is not necessarily on the 27th of Ramadan as commonly assumed.

A significant finding in historical and astronomical research suggests that the first revelation likely occurred on August 10, 610 CE, based on lunar cycle calculations and historical records that align with a full moon night during that period. This alignment with a full moon night suggests that Laylatul Qadr follows a predictable lunar cycle rather than fluctuating dates. Historical records and astronomical data indicate that this night was observed on the 27th of Ramadan, which explains why many continue to seek it around this time.

There is a special post dedicated to Laylatul Qadr for more insight. Click here.

4. The Calendar Controversy: Was Ramadan Always a Lunar Month?

📖 “Indeed, the number of months with Allah is twelve months in the decree of Allah the day He created the heavens and the earth; of them, four are sacred.” (Qur’an 9:36)

Key Observations:

✅ The pre-Islamic calendar was not strictly lunar; it included intercalation to align with the solar year.

✅ This means that Ramadan, at the time of the Prophet, would have followed a more consistent seasonal pattern.

✅ The shift to a purely lunar calendar disconnected Ramadan from its original position in the seasonal cycle.

These insights challenge the modern assumption that Ramadan was always based on a strictly lunar cycle and suggest that its original timing may have been more stable within the year. Historical records indicate that pre-Islamic Arabs used an intercalated calendar, aligning lunar months with the solar year to maintain seasonal consistency. This system ensured that Ramadan consistently fell in the same period each year, a practice that was later abandoned with the shift to a purely lunar calendar.

5. Breaking the Fast: When is ‘Night’?

📖 “Then complete the fast until the night.” (Qur’an 2:187)

Key Observations:

✅ The Qur’an specifies ‘night’ (layl) as the time to break the fast, not ‘sunset’ (maghrib).

✅ Layl in the Qur’an consistently refers to a period of actual darkness, not the brief moment after sunset.

✅ Observations from nature suggest that a clearer threshold, such as the disappearance of twilight, aligns better with Qur’anic terminology.

This finding challenges the widely practiced notion of breaking the fast immediately at sunset and encourages a deeper reflection on natural indicators for timing worship. One practical method to determine the correct time for breaking the fast is to observe the sky: when twilight fully disappears and complete darkness sets in, marking the true onset of night (layl), the fast can be broken. This approach aligns with the natural rhythm described in the Qur’an and avoids rigid adherence to fixed astronomical calculations.

6. Exemptions and Flexibility in Fasting

📖 “But if any of you is ill or on a journey, then an equal number of days are to be made up later. And for those who are able to fast with hardship, there is a ransom: feeding a needy person…” (Qur’an 2:184)

Key Observations:

✅ Fasting is not meant to be an undue hardship.

✅ Those who are sick or traveling can make up missed fasts later.

✅ An alternative form of compensation (feeding the needy) is permitted.

The Qur’anic approach to fasting is compassionate and flexible, accommodating different circumstances without excessive legalism.

7. The Transformative Power of Fasting

📖 “And that you fast is better for you, if only you knew.” (Qur’an 2:184)

Fasting is more than an obligation; it is an opportunity for personal transformation, heightened awareness, and a deeper connection with Allah. The Qur’anic guidance on fasting is simple, flexible, and rooted in natural cycles—free from the rigid constraints later imposed through human interpretation.

🚀 Are you ready to embrace fasting as the Qur’an prescribes and realign your practice with divine wisdom? The Qur’an presents fasting as a limited period of devotion, deeply tied to Laylatul Qadr and the natural cycles of time. Unlike later interpretations that expanded it to a full lunar month, historical and linguistic evidence suggests that the core fasting period was originally ten days. Additionally, the Sunnah practice of fasting six days in Shawwal reinforces this understanding.

Start by observing the natural signs of dawn and nightfall to determine your fasting schedule, reflect on the spiritual benefits of self-restraint, and strive to make fasting a transformative experience in your life.